Legal Research And Writing For Paralegals

Contracts are terribly intimidating to most of us–and you could argue that's at least a little by design. Most lawyers bill by the hour, after all, and they reuse text from older contracts rather than writing new ones. The resulting legalese requires more lawyers, who serve to translate and negotiate a path through all that jargon. The cost–and inefficiency–of that process has spurred on a slew of startups aimed at "fixing" contracts. That includes Outlaw, which raised $2 million in seed series funding late last year and has corporate clients like the real estate broker Compass, Virgin Hotels, and Barclays, along with the design and development firms Smart Design and Work & Co.

Outlaw is notable both for the scope of what it's trying to do, and how it's trying to do it. The service is not a contract depository–in other words, it's not an app that you can download to create a contract for selling your car. It's really a contract platform, designed for medium-sized businesses that send out a frequent cadence of contracts. Once a contract is set up in Outlaw, the software allows the contract to be tweaked in plain language between two parties, without involving legal council, through an interface that's familiar to anyone who's used Google Docs.

"I come from a freelance consulting background. Contracts for a design, creative, or humans in general are probably the most intimidating part of doing business with someone," says Outlaw cofounder and design lead Dan Dalzotto. "Slapping a 10-page contract in front of someone…I call it a bit of a relationship-killer because it's almost like proposing on the first date."

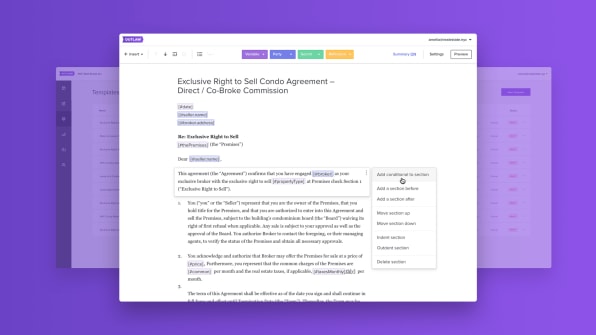

Dalzotto and his partner Evan Schneyer, who are developers rather than legal scholars, thought there must be a better way–so they prototyped it. Rather than a PDF or Word doc you sign, Outlaw deconstructs a text contract into its bits of interdependent logic, or what we'd simply call "code" in just about any other modern context, allowing names and paragraphs to be swapped in and out like pieces of a puzzle.

"We looked to GitHub and said, 'We use that for code; let's use that for contracts,'" says Dalzotto. "Because the principles are the same."

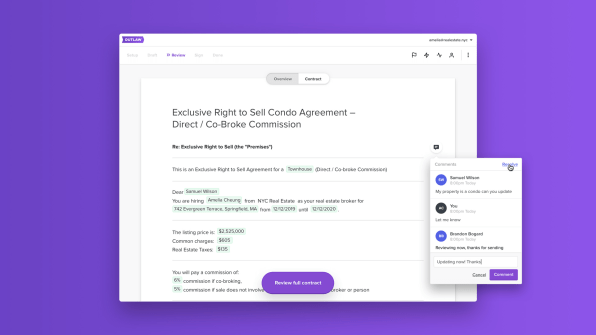

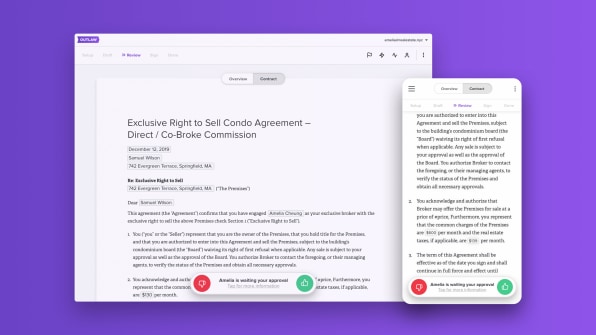

When you open an Outlaw contract that's been sent to you, it's broken into two tabs, Overview and Contract. In the Overview tab, you see just a few variables to change. For instance, for a realtor contract, you would put in the buyer's and seller's names, an agreed-upon price, and a commission. It's presented in simple language that's easy to fill in. Only when you tap on the Contract tab do you see the whole contract, which has been populated with all your new variables in tandem.

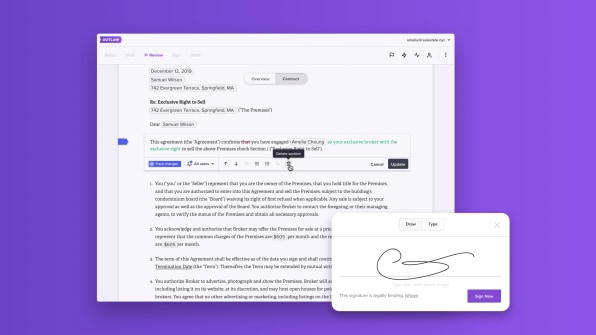

In the Contract tab, you realize just how closely the interface resembles Google Docs, from all sorts of Material Design cues to its inline threaded comments. "We looked at that sort of [Google Docs] paradigm and thought, you know what, Outlaw needs that as well," says Dalzotto. "We're essentially bringing together all these features from other worlds and putting it into Outlaw. A lot of this stuff has been solved, just not for contracts."

Because Outlaw's contracts are essentially code, the UI itself can do a lot to protect both sides of the contract, as the changes are ironed out within the text editor. As soon as any section is "red lined," or rejected by one party, it has to be resolved before the contract can be signed. Since all changes are version tracked, there's no way to sneak in old, deleted language to a late revision contract. And if, say, section 10 of a contract is deleted, it will automatically flag anything in the contract referencing that defunct section and reference renumber sections 11, 12, 13, and 14 accordingly.

Outlaw isn't marketed for the general public. It's very much an enterprise product, licensed according to company size. It's designed to take the weight off internal legal councils, allowing lawyers to set up a contract just once, then empower salespeople and other frequent deal signers to handle those contracts with less oversight. However, from a 30-minute demo with Dalzotto, in which we negotiated our own mock real estate deal, its interface proved to be perfectly consumer friendly. As a layperson, I had a strong understanding of exactly what was changing with the contract, without any learning curve–even if Dalzotto refused to budge on his commission of 6%.

Legal Research And Writing For Paralegals

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90309870/this-startup-is-helping-barclays-compass-and-more-close-deals-90-faster

Posted by: hidalgophers1974.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Legal Research And Writing For Paralegals"

Post a Comment